LAS CRUCES – As Spaceport America gets its finishing touches, awaiting the day that Virgin Galactic launches passengers beyond the stratosphere, more states are looking at entering the space industry, with a spaceport at the cornerstone of their plans.

“It almost looks like wildflowers growing across the U.S., if you look at all the ones talking about it,” said Christine Anderson, executive director of Spaceport America.

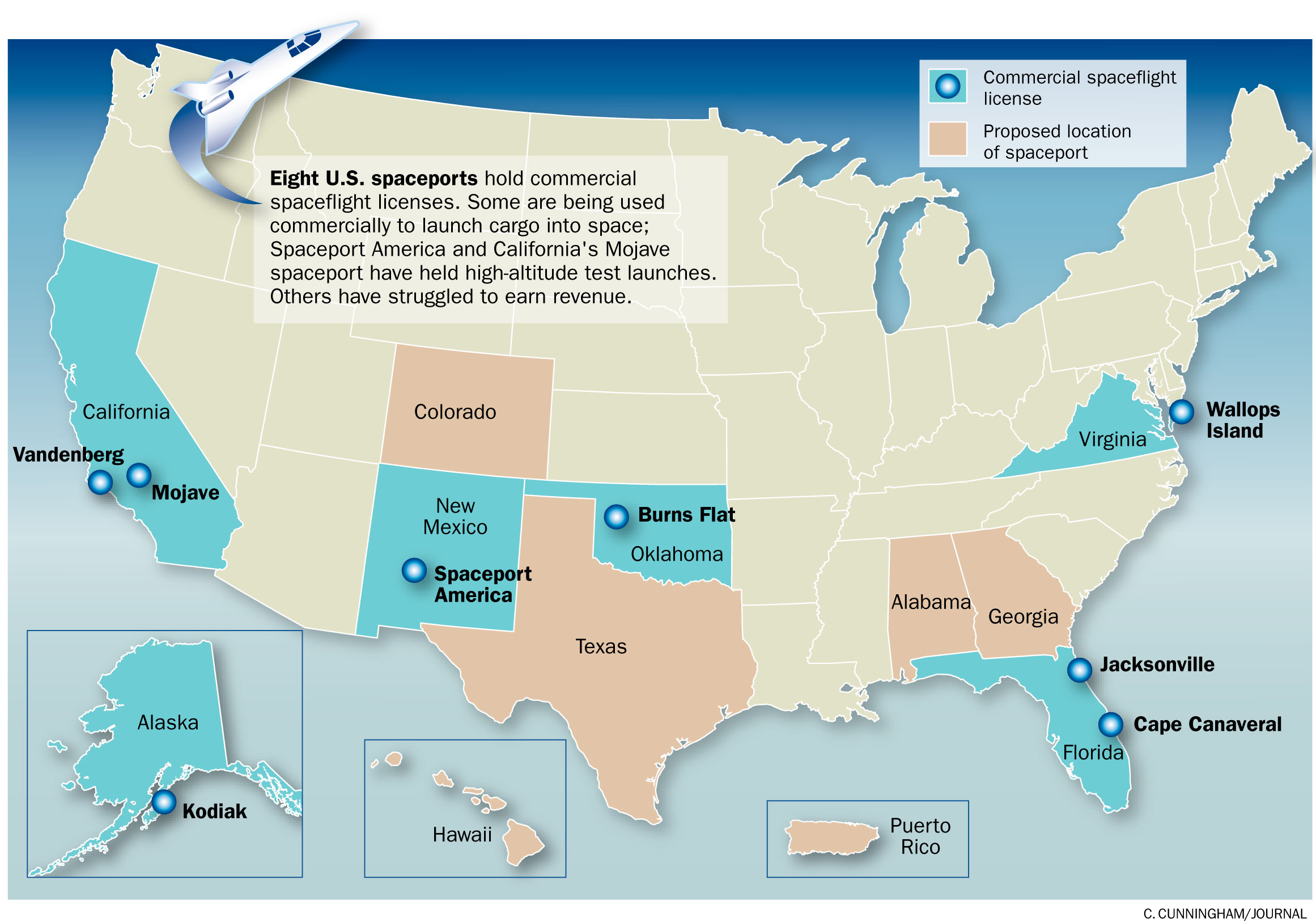

Hawaii, Georgia, Alabama and Puerto Rico are mulling spaceports. Two spaceport projects are in the works in Texas, in Midland and Houston. Spaceport Colorado expects to apply for a Federal Aviation Administration commercial license by year end.

The motivation driving these projects is the chance to get an early edge in an emerging commercial space flight industry that – beyond space tourism for the few who can afford it – could have sweeping commercial, civil and military applications. But the risks are big, too: Of the eight U.S. locations that currently hold commercial licenses to fly into space, only a few are active, while others have languished as the industry makes its slow march toward successfully flying people to space and back.

“I think they’re seeing a nascent industry, and they want to get in on the ground floor and be there for the growth,” said Art Waite, who directs the aerospace division of BRPH Architects-Engineers Inc., which builds spaceport facilities.

Unlike modern airports, no spaceport is one-size-fits-all, as every launch vehicle is unique. But with the commercial space industry in its early stages, and so few spaceflight companies at the forefront, will new spaceports oversaturate the market?

Andrew Aldrin, astronaut Buzz Aldrin’s son and director of business development at United Launch Alliance, summed up the hopes and limitations of the emerging commercial space industry at a recent symposium in Las Cruces: “Many of us in this room believe there is a passenger space flight market out there,” he said. “But we don’t know until someone goes up.”

“The criticism that I have heard is that there is too much capacity already,” said Michael López-Alegría, a former NASA astronaut and current president of the Commercial Spaceflight Federation. “By and large, there is not a ton of commercial traffic and zero human commercial space traffic.”

Virgin Galactic had expected to be flying passengers by Christmas but is still in the testing phase. Owner Richard Branson said in September he hoped to have his spaceship in space “within the next handful of months,” although not this year.

Eight markets

A study funded by the FAA’s Office of Commercial Space Transportation forecasts demand in eight markets: space tourism; basic and applied research; education; aerospace technology testing; media, including advertising, film and television; satellite development; earth imagery for commercial, civil and military applications; and point-to-point global travel.

Right now, Virgin Galactic’s $250,000 tickets essentially secure a place in line for a future trip to a view: a glimpse of earth from sub-orbital space. The FAA study estimates that only about 8,000 very wealthy people across the globe have the kind of spending patterns that suggest they would drop a quarter of a million dollars on a short trip to space.

But the business model Branson and other players envision doesn’t begin and end at passenger journeys to space and back. The industry wants commercial launches of satellites into orbit and the sub-orbital point-to-point travel that would make long journeys, from Spaceport America to Tokyo or Dubai, for instance, incredibly fast.

“We may never pull it off,” Branson said of point-to-point travel in a September interview. “But we’re going to go for it.”

Companies like Virgin Galactic, XCOR and SpaceX are testing the reusable vehicles that would open these markets, but timelines have been frequently pushed back. No one wants to rush passengers into space and risk their safety.

“If we have a failure early on in this program,” said Aldrin – referring to commercial passenger spaceflight generally – “it will be really difficult. We’ll be down for a long time.”

U.S. licensed spaceports

New Mexico’s Spaceport Americaplans to carve out a niche in the space tourism market, with Virgin Galactic as its anchor tenant. The spaceport has hosted 19 vertical test launches so far.

Alaska’s Kodiak spaceport faced possible closure until it secured a deal with Lockheed Martin in 2012 to launch the defense contractor’s Athena rockets.

Florida’s Kennedy Space Center is trying to find ways to rent its facilities for commercial launches. SpaceX has shipped payloads to and from the International Space Station (ISS) from Kennedy.

Florida’s Cecil Field in Jacksonville is an airport that offers a runway long enough to permit horizontal launches of space vehicles that would take off and land like airplanes.

California’s Mojave spaceport is currently the site of Virgin Galactic’s vehicle test launches.

The California Spaceport at Vandenberg was the first to hold a commercial space launch site operator license from the FAA, and offers satellite processing and launch services for commercial and government clients.

Virginia’s Wallops Island spaceport is another takeoff point for commercial trips to the International Space Station (ISS). Orbital Sciences Corp. ships to ISS from here.

Oklahoma’s Burns Flat spaceport has not delivered on the economic development promises tied to the project when it was conceived in 1999. Facilities are deteriorated and largely unused.

Unpredictable

The unpredictability of the emerging commercial space industry complicates the spaceport business. Each location is trying to find its own niche, and some are better positioned for success than others.

Florida’s Kennedy Space Center has multiple facilities, a legacy of NASA’s heyday, and is trying to figure out how to rent its launch pad to commercial spacelines.

Houston’s Ellington Field hopes to obtain a spaceport license “to be able to operate at any given time if and when … an operator decides they need to be flying out of Houston,” said Arturo Machuca, manager of business development for the Houston Airport System, which runs Ellington Field.

Others haven’t quite lived up to their promise. Oklahoma’s Burns Flat spaceport – – conceived in 1999 as a way to attract commercial space business to the region – is marred by blighted buildings and derided by town officials. Last year, elected officials in Alaska had threatened to shutter the state’s struggling Kodiak Spaceport until it secured a contract with Lockheed Martin for rocket launches.

Spaceport America’s Anderson said New Mexico is competitively positioned to capture business in the markets that commercial space flight will ostensibly open up. She has fielded calls from other states that want to learn about New Mexico’s model, in which $209 million in taxpayer money funded a spaceport tailored to anchor tenant Virgin Galactic’s specifications, and liability protections make the state more attractive to manufacturers and suppliers.

Spaceport America’s goal is to draw “terrestrial space tourists,” Anderson says, as well as additional tenants like SpaceX, which is poised to launch high-altitude test rockets from the site before the end of the year.

The spaceport is now paying about 75 percent of its $1.85 million operating budget with revenue, Anderson said. A state appropriation of $459,000 each of the past three years has covered the remaining 25 percent.

“All the money can’t come from commercial space,” Anderson said. “Airports don’t make all their money through airlines; they make it through concessions and other things. Ours is the tourism side.”

Spaceport America has advantages compared with some of the other locations that may come online, said James Peach, economics professor at New Mexico State University. A higher altitude, restricted airspace nearby and the state’s long history with space flight are among them.

Another advantage is that “ours is built,” he said. “A lot of the others are simply proposals.”

But there are still many unknowns, including how soon commercial launches of passengers into space will begin.

Peach added, “Bottom line is ours could be very successful, or it could be a flop.”

Copyright © 2013 Albuquerque Journal

By Lauren Villagran / Journal Staff Writer – Las Cruces Bureau

For the original Article click Here