Our space correspondent meets the controllers of the International Space Station as they steer away from deadly space junk and keep astronauts alive.

It could be the most boring reality TV show in the world, if the stakes were not so high. On a huge screen at one end of a giant room is an image of a white-walled corridor, harshly lit by strip lights and cluttered with equipment, ducts and wires. Occasionally someone drifts into view, adjusts something, and then moves out of vision. There is no plot, tension or jeopardy. However, since the picture is beamed live from the International Space Station (ISS), drama is not what the controllers on the ground are after.

“The crew has just had lunch, it’s a routine day with not a lot of activity going on, which is good,” explains ground control officer Bill Foster, as we sit in the viewing gallery overlooking the ISS mission control room in Houston, Texas. In front of us, some 20 people sit behind consoles surrounded by banks of computer screens displaying a mass of numbers, graphs and tables.

Foster’s role is to coordinate control room and communications systems to make sure everything is working smoothly, but he has been allowed a break to chat to me. He points out the blank middle section of one of the large screens at the front of the room. “If anything pops up there, the computers on board the station have determined that something’s not working right and it’ll come up as either a black, yellow or red warning,” he says. “Red is bad.”

This room has been staffed continuously, around the clock, since the launch of the first sections of the ISS in 1998. It sits at the heart of the mission’s operations and oversees astronauts’ daily routines regardless of events on Earth. “We have to make sure they’re healthy, they’re safe, they have a sound platform to do the work we’ve sent them up there to do,” says Foster. “You see the people here, that’s just the tip of the iceberg of what’s happening.”

Around the world hundreds of other people are also working to support the mission. Even on a routine day, in other rooms at the space centre, mission controllers are planning station procedures weeks and months ahead. At the ISS mission control in Moscow, staff are overseeing the Russian segment of the space station and scheduling Soyuz supply missions. The work of any European astronauts and the Japanese space laboratory is being coordinated by others in Germany and Japan. Routines for the station’s robotic arms are being developed by engineers in Canada.

Deadly debris

Simply keeping the ISS in orbit is a challenge. Even at around 400 kilometres above Earth, there are residual traces of atmospheric particles that act as a drag on the station’s vast structure. “If left alone the station would eventually come back into the atmosphere over a period of months,” says Foster. “We’ve got a trajectory officer who’s watching that and designing manoeuvres when we need to add some thrust.”

The Trajectory Operations Officer (known as TOPO) is also responsible for ensuring that the station dodges fast moving pieces of space junk that could rip a hole in the side of the orbiting lab. The procedure involved is referred to as a Debris Avoidance Manoeuvre, or DAM – an appropriate acronym as it sometimes turns out.

“We were relying on the Russian thrusters to move us out of the way,” recalls Foster of an incident in the last 12 months. “Half of the

“It was an interesting shift to work on,” he adds dryly.

Despite the international nature of the ISS, if something goes wrong the buck stops in this room. Specifically, it stops at a desk in the middle of the room marked Flight Director. As we watch from the viewing gallery, the man currently occupying this chair is leaning back with his hands behind his head looking remarkably relaxed.

Although “Flight” is ultimately in charge, those with this nickname are not normally allowed to talk to the astronauts in orbit. That responsibility rests with the Capcom – or Capsule Communicator – a job title with its origins in the earliest days of human space exploration when astronauts took short flights in tiny metal capsules. The Capcom acts as a single point of contact to and from the ground to eliminate any chance of confusion, particularly in emergencies.

Communications to and from space are possible thanks to a dedicated network of satellites. These Tracking and Data Relay Satellites sit in a geostationary orbit, high above the ISS, and allow almost continuous communications between the station and the ground.

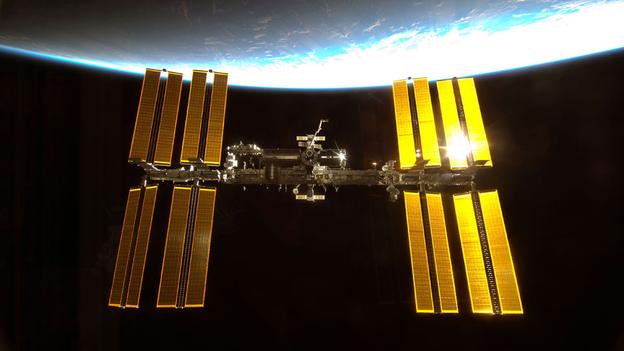

Although watching activity inside the space station may be tedious, live pictures from a camera on the outside of the station – displayed on another one of the giant screens at the front of the room – are altogether more interesting. As we chat, Foster points out that the station is orbiting almost directly above us, its path taking it towards the Gulf of Mexico. We watch as it passes down the US east coast, the land obscured by streaks of white cloud.

“It’s one of the nice things about this job,” he says. “If we’re coming up over the United States at night, they’ll pan and tilt the camera to catch some of the cities on the ground and we’ll ‘ooh and ahh’ over the lights.”

Things are about to get busy. But before Foster returns to his console to work on an operation to move a robotic arm on the outside of the station, I ask him whether he would rather be up in space. He doesn’t hesitate to reply.

“The thing I’d like to do most is be in space” he exclaims. “The nice thing about the people in this room is we’re all agreed that we have the second best job in the world.”

By: Richard Hollingham

To view the original article CLICK HERE