The entrepreneurs of new technologies like to flock together. Those behind “New Space” are no different. And the place they are clustering is the middle of a desert

IT BEGAN with a boom. In 1947 Chuck Yeager, a pilot in the newly formed United States Air Force, became the first man to break the sound barrier and thus create a sonic one. He flew from Edwards Air Force Base in the Mojave Desert, America’s main center for experimental military flights. This base was out of the way of prying eyes and surrounded by landscape into which a crash (and there were many) would not inconvenience anyone except the pilot, if he failed to eject. And its very isolation promoted an intensity of purpose. It was perfect.

Others now hope to use that perfection to create a different sort of boom—a commercial one. For the Mojave Desert seems to be emerging, in the unplanned way that these things will, as the site of a cluster of Colonel Yeager’s spiritual descendants. These individuals, the entrepreneurs of what has come to be known as New Space (to distinguish it from the old, hidebound, government-led way of doing things), are a curious crossbreed of starry-eyed dreamer and hard-nosed businessman, often in the same individual. Their collective goal is to find novel ways of getting into the cosmic void, and then profit from them

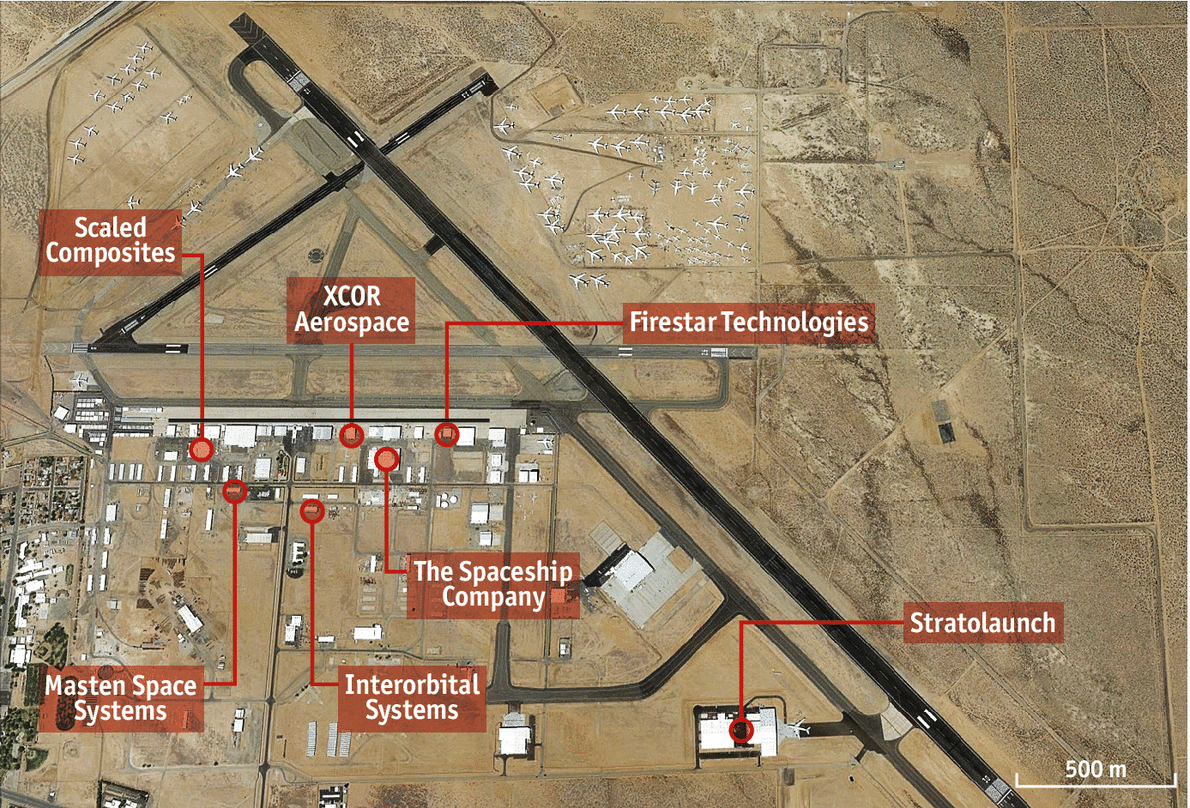

Their centre of activity is not actually Edwards. That is still an air-force base, and thus off limits to them. Instead they have gathered 30km (20 miles) north-west, in the town of Mojave itself, around the civilian airfield, now dubbed the Mojave Air and Space Port (see picture above).

At the moment, 17 rocket and space-related companies operate in the Air and Space Port, though not all have their headquarters there. Some are the aerospace equivalents of the garage start-ups that brought Silicon Valley to life—but with a considerably higher chance of interesting explosions. Others are well-capitalised, and have been in business for a while. Most hope to make their money, at least at first, from launching satellites. Two, though, plan to enter the glamorous trade of taking tourists into the void.

The knight’s tour

The more advanced of these two is Scaled Composites, which was founded in 1982, by Burt Rutan, an aerospace engineer, and bought in 2007 by Northrop Grumman. Scaled Composites has designed and built SpaceShipTwo, a rocket-plane intended to carry paying passengers to the giddy heights of 100km above Earth (an altitude officially defined as being the inner edge of outer space) using what is known as a hybrid rocket engine.

Existing rockets are either solid-fuelled, with propellant and oxidant mixed together as a block, or liquid-fuelled, with propellant and oxidant stored separately and then mixed in the engine’s combustion chamber. Solid-fuelled rockets are easy to handle on the ground, but hard to control in flight because, once ignited, their fuel burns until it is exhausted. Liquid-fuelled rockets are the other way round, and also tend to be more powerful. SpaceShipTwo’s hybrid tries to have the best of both worlds, with a solid propellant and a liquid oxidant. Its power can thus be regulated by altering the oxidant’s flow.

SpaceShipTwo is an air-launched craft. It is lifted to an altitude of 15km by a special twin-hulled aeroplane, with a wingspan of 43 metres (141 feet), called White Knight Two (also built by Scaled Composites), and then released to fend for itself. Only after that is its rocket ignited for the journey to space. Two powered test flights and numerous unpowered glides suggest this idea works. Virgin Galactic—a British firm founded by Sir Richard Branson, a serial entrepreneur—which paid, through its subsidiary the Spaceship Company, for Scaled Composites to develop the craft, plans to start flights next year for those with the necessary $250,000 to buy a seat.

Scaled Composites’ (and Virgin’s) main local rival in the suborbital tourist market is XCOR, run by Jeff Greason, an engineer who helped develop the Pentium microprocessor for Intel. Mr Greason’s proposed vehicle, Lynx, has yet to fly—though he plans to correct that omission in 2014. It, too, is a rocket-plane. But it is a liquid-fuelled machine designed to take off from a runway under its own power.

SpaceShipTwo and Lynx are, however, toys compared with what is proposed by Stratolaunch Systems. This company, Mr Rutan’s current project (in which he is collaborating with Paul Allen, a co-founder of Microsoft), proposes to take the air-launched-rocket principle and push it to the limit. Mr Rutan and Mr Allen are acting as impresarios for a show that includes Scaled Composites and another well-established firm, Orbital Sciences. Orbital already makes an air-launched rocket, Pegasus, which is used to put satellites into orbit, and the firm also has a contract to re-supply the International Space Station.

Scaled Composites’ contribution will be a giant version of White Knight, called Roc. This will have a wingspan of 117 metres, making it, by that measure, the largest aeroplane that has ever flown. Stratolaunch has therefore built one of the biggest aircraft hangers in the world at Mojave, to accommodate it.

The battle between rocket-planes, such as SpaceShipTwo and Lynx, and the more familiar type of space rocket, an upright cylinder with a cone at the top and engines at the bottom, goes right back to the beginning of serious rocketry. Colonel Yeager broke the sound barrier in a rocket-plane, the Bell X-1, but it was the successors to the V2, the first long-range military rocket, designed by Wernher von Braun, which actually put satellites and astronauts into orbit—and modern versions of these, too, are under development at Mojave.

Masten Space Systems, the creation of David Masten, an engineer with expertise in project management, wants to give the traditional upright rocket design one of the great advantages that rocket-planes have over it: controlled landing. This would mean that hardware now lost during launch (the rockets used to put satellites into orbit usually end up at the bottom of the sea) could be flown over and over again. Using a series of experimental vehicles called Xombie, Xoie, Xaero and Xeus, Mr Masten has been experimenting with liquid-fuelled rockets that can both lift off normally and land under their own power in the way that the Apollo project’s lunar modules did.

Other companies are also trying to improve the von Braun configuration. Firestar Technologies, run by Greg Mungas, is developing a liquid fuel that consists of premixed propellant and oxidiser. This requires only one tank, and no complicated mixing mechanism in the motor, which simplifies the engineering. Meanwhile, Interorbital Systems, led by Roderick and Randa Milliron, is attempting to modularise things, by designing small, cheap rockets that can be strapped together in bundles, using as many as are necessary to lift a given payload into orbit.

Mojave, then, looks like a proper technology cluster, with firms both competing and collaborating, and a mixture of large and small companies. Much of the money still comes from rich individuals, such as Mr Allen, who would probably not mind being described as “space cadets”. But a combination of high-end tourism and the market for commercial satellite launches (worth about $3 billion a year) means that if they can get the technology right, some, at least, of these firms should soon become real businesses, with proper revenue streams and maybe even profits. To do so, however, they will have to deal with competition from elsewhere, for two of the biggest and richest space cadets are eschewing the Californian desert.

One of them is Jeff Bezos, Amazon’s founder. His space firm is called Blue Origin, and its launch facilities are in Texas. Like Mr Masten, but with a lot more money behind him, Mr Bezos is working on a rocket that can both take off and land under its own power. He calls it New Shepard, after Alan Shepard, America’s first astronaut.

The Falcon’s prey

The other man outside Mojave’s orbit is Elon Musk, one of the entrepreneurs behind PayPal. Mr Musk’s firm, SpaceX, is based in Hawthorne, a suburb of Los Angeles. He currently launches from Vandenberg Air Force Base, in California, and Cape Canaveral Air Force Station, just south of the Kennedy Space Centre, NASA’s launch facility in Florida, but both he and Mr Bezos have had their eyes on pad 39A at Kennedy, from which Space Shuttles were once dispatched. And on December 13th NASA picked SpaceX.

Mr Musk’s route into space at the moment is a traditional-looking liquid-fuelled rocket called Falcon (though he, too, is experimenting with a rocket, called Grasshopper, that takes off and lands under power). And he already is properly in business. Craft launched by Falcons have resupplied the International Space Station and Falcons have also put two communications satellites into orbit in 2013.

Mr Musk plans to send people into orbit, too—perhaps as early as 2015. And he aspires to send them farther than that, for his sights are set ultimately on Mars.

Whether there is money to be made on Mars is not clear. A round-trip would take years, so only the most dedicated tourist would be interested. And whatever minerals might be on the surface, mining them and returning them to Earth would be formidably expensive. Mr Musk himself has said he aspires to die there, though “not on impact”. A retirement home for billionaires, perhaps?

By:

To view the original article CLICK HERE